featured item

Why collect antique maps? The alternative to GPS and SatNav

Posted by Chris on 14/02/2025

There is a much more organic way of getting around with our phones, Google Maps, GPS or car satnav.

Antiques.co.uk's founder, Iain Brunt, explores the upside to collecting antique maps, and how, like record players or writing letters, maps can help us connect more organically to the real world.

“A few times I have wondered what would we do if we were lost and had no telephone signal. Or imagined what we'd all do if there was an electrical or satellite outage, and we could no longer connect to Google Maps with our phones...

‘What happened to studying a map?’ I asked myself. I pondered whether any of us still actually have one.

I spend a lot of time outdoors, especially up in the mountains around Geneva, so I’ve encountered that situation many times. Now, I never leave home without a compass and map when setting out on a hiking trip, just in case.

Pictured: the oldest surviving Ptolemaic world map

My fascination with antique maps

Maps have always been a fascination of mine: the details they contain are incredible, especially when you consider the eras in which they were created. It is only recently that some parts of the world were even mapped out. That's why I love antique maps.

The oldest surviving Ptolemaic world map was redrawn according to his 1st projection by monks at Constantinople (modern day Istanbul) under Maximus Planudes around the year 1300.

Scotland – as we know it now – has an extra piece added on, which we assume to be the islands yet to be identified.

It was during the Age of Discovery, from the 15th to 18th centuries, that world maps became increasingly accurate. Exploration of Antarctica, Australia, and the interior of Africa by western mapmakers followed in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

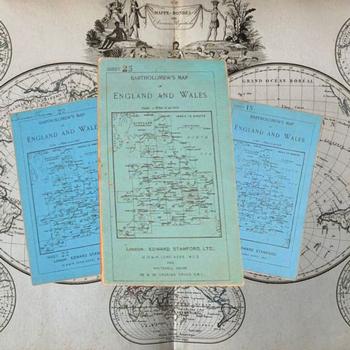

Pictured: 1904-1920 Bartholomew’s “Half-Inch to Mile” map of England & Wales, £500

Antique road maps

Like many people, my father always had a road map in the boot of his car (like this set of 1904-1920 Bartholomew’s “Half-Inch to Mile” map of England & Wales, pictured above), which now seems a very sensible idea.

And some of us beyond a certain age refuse to use satnavs, relying instead on the old fashioned way of tracing our routes across the red and blue lines of the printed map booklets.

There is something much more connected to the landscape, and nature, about finding your way around the countryside like that.

You only have to imagine running out of battery on your phone, or getting stuck somewhere rather remote out in the hills, to come face to face with the very real danger that would bring.

Pictured: Celestial globe with clockwork 1579, Metropolitan Museum of Art (NYC) by Gerhard Emmoser.

Terrestrial and celestial antique globes

Antique globes were my fascination when I was a child, and I remember constantly spinning them round and around – probably to my parents’ annoyance.

The are two types of globe: terrestrial and celestial. A terrestrial globe depicts a spherical map of the earth, and celestial globes map the stars spherically using the earth as an imaginary centre of the universe.

Modern terrestrial globes were possibly first created by the Flemish cartographer Gerardus Mercator during the mid-1500s.

Pictured: a rare antique embroidered map sampler of England & Wales, signed and dated M. York, 1804; £295

How to start collecting antique maps

Personally, I think maps are extremely good value - but they are vulnerable as they are made of paper. Unfortunately, that deteriorates quickly, so I would strongly recommend any new collector to consider collecting antique maps now.

If I were starting to collect antique maps, I would concentrate on a particular area. When I was younger I was fascinated by pirates, so I collected maps of the Caribbean. And I am so glad that I did, as they are now quite rare – and valuable.

Happy hunting on Antiques.co.uk – you’ll find some excellent maps listed for sale with us."

Here are my top 5 antique map and globes to start collecting:

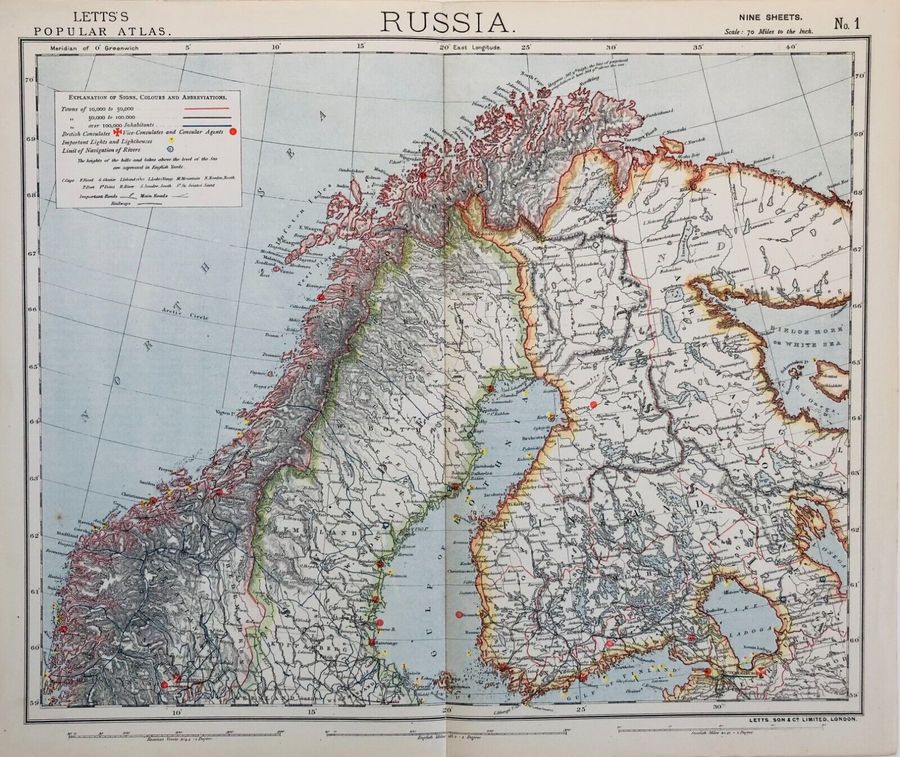

1. Lett's Map of Russia, North Sweden, Norway, Finland, Lapland, Jemtland c.1833. Price: £140

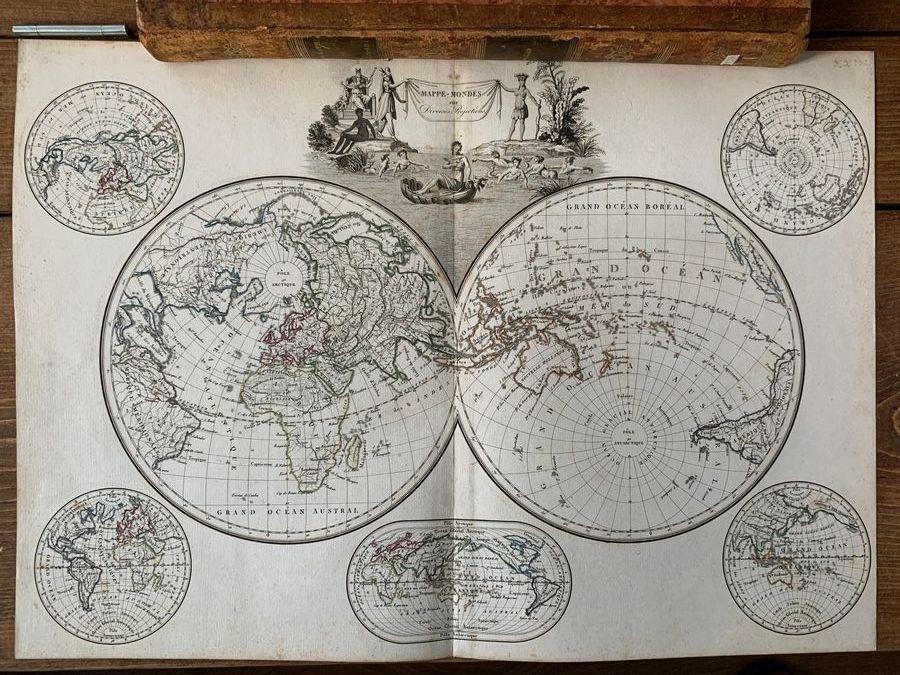

2. World Map, Malte-Brun, Atlas Complet du Precis de la Geographie Universelle, (Paris) 1812. Price: £175

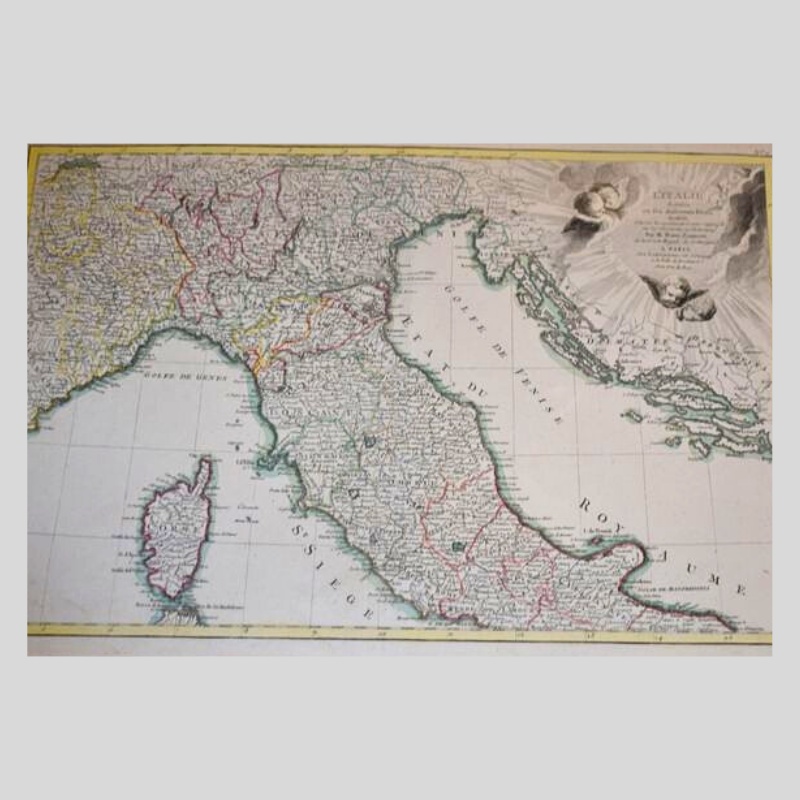

3. Map of central and northern Italy by Zannoni, 18th Century. Price: £100

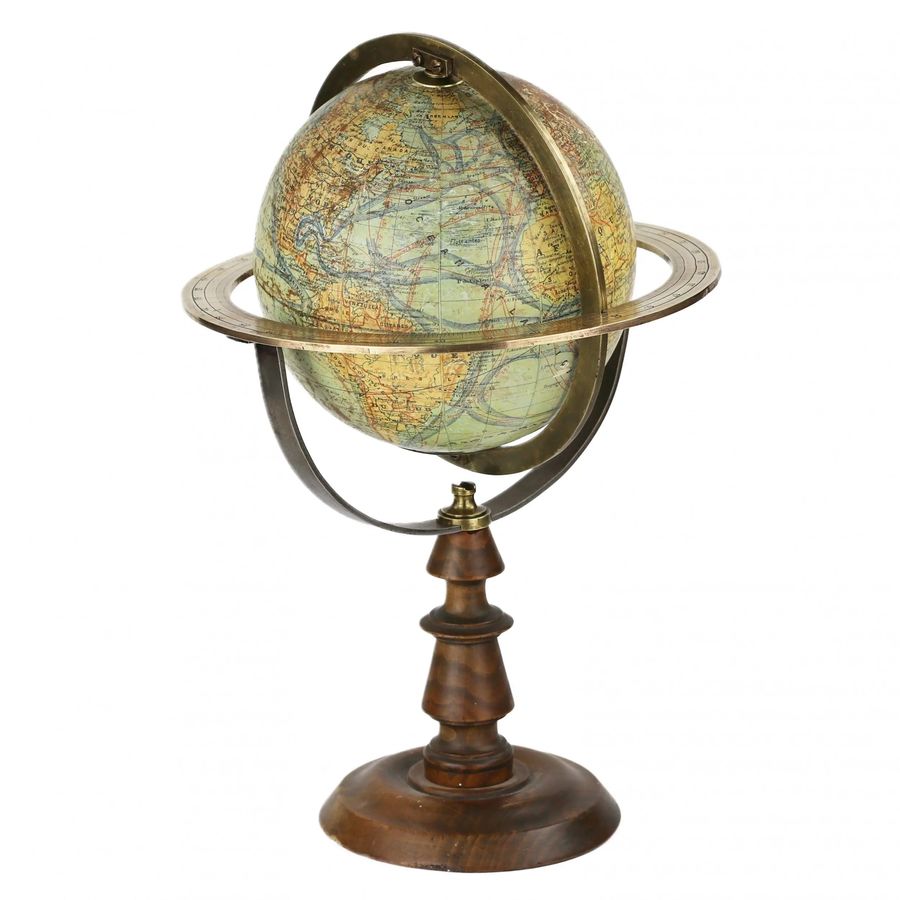

4. 1930s Globe on stand. Price: £800

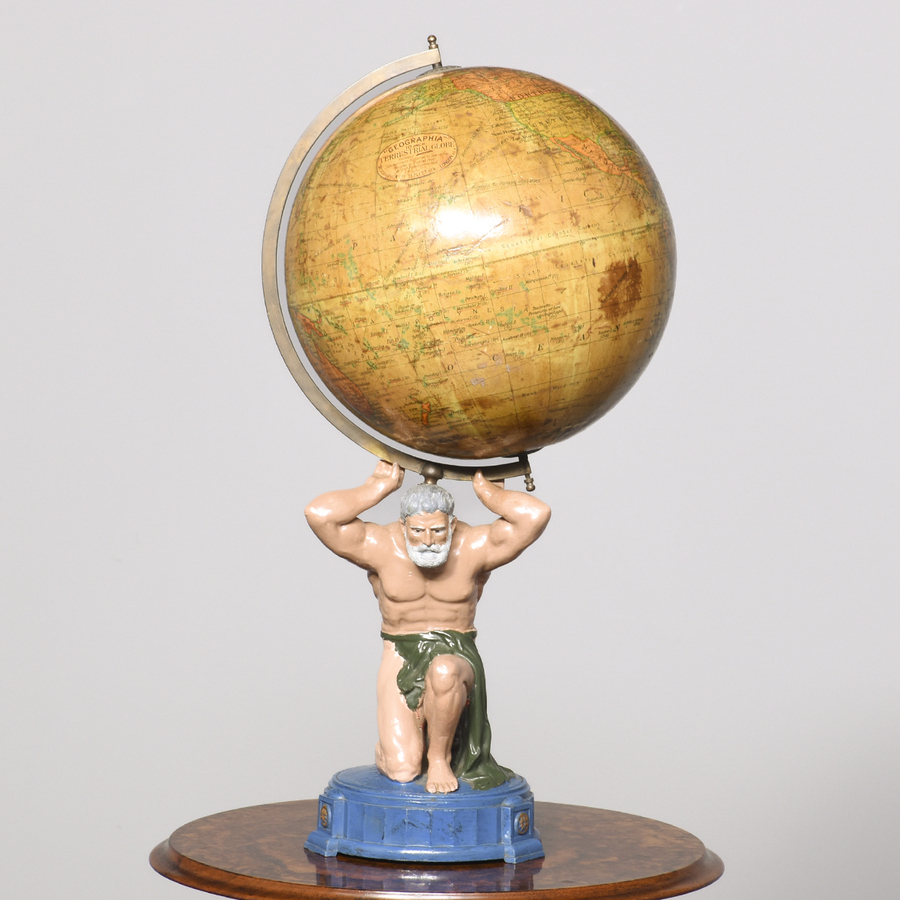

5. French Antique Globe by J. Forest, c.1900. Price: £915

> Explore all antique maps

> Explore all antique globes